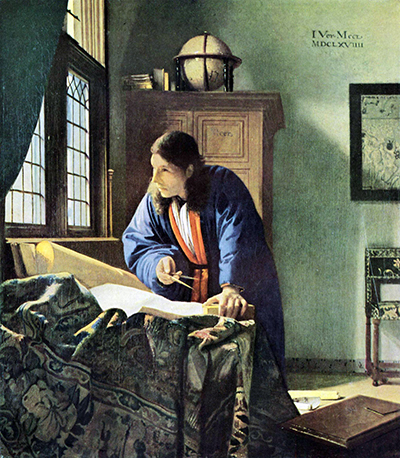

They said he painted with light. Here’s the thing though, you can’t paint with light; you have to paint with, well, paint. Anyone who is familiar with Johannes Vermeer’s paintings, however, understands what is being said here. He is renowned for his masterly treatment and use of light in his work.

Vermeer married a woman who came from great wealth. Her family staked Vermeer in an art dealership business. The couple moved in with the in-laws, who lived in a rather spacious house at Oude Langendijk, in Delft. Here Vermeer lived for the rest of his life, producing paintings in the front room on the second floor. It is notable that nearly all of Vermeer’s paintings were created in this room. All of the subjects faced the same direction, toward the light which fell, golden and lazy, from the finely framed windows. The angle from which the subject was viewed was also strictly identical.

There is no other seventeenth-century artist who so lavishly used exorbitantly expensive pigments such as lapis lazuli, or natural ultramarine. Vermeer not only used these in elements that are naturally of this color but also as base colors which helped achieve the luminous qualities in his paintings. In this way he implemented Leonardo da Vinci’s observations that the surface of every object partakes of the color of its adjacent objects. This means that no object is ever seen entirely in its natural color, and the beauty of an object relies in part on its surrounding objects.

In the above painting (The Girl with a Wineglass), for example, the red satin dress is underpainted in natural ultramarine then painted again with shades of red and vermillion creating an astounding realism.

It is also notable that Vermeer worked very slowly and meticulously. Exercising extreme patience and persistence, he produced only three paintings a year. In these ways, Vermeer created a world more perfect than any he had witnessed. Mundane domestic or recreational activities became imbued with a poetic timelessness.

Vermeer was relatively unknown to art history for quite some time. While he achieved some very local recognition around Delft and The Hague, his modest success gave way to nearly total obscurity after his death. He was barely mentioned in Arnold Houbraken’s 17th-century tome on Dutch painting (Grand Theatre of Dutch Painters and Women Artists), and was thus omitted from subsequent history of Dutch art for nearly two centuries.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that Vermeer was rediscovered by two art historians, Gustav Friedrich Waagen and Théophile Thoré-Bürger, who published an important essay on Dutch art. From that time Vermeer’s recognition has grown and he is now widely considered a master of the “Dutch Golden Age” of art, which included painters such as Rembrandt.

The chief direction of this era (1615–1702) was away from strict religious subjects. Dutch Calvinism forbade religious paintings in churches, and though biblical subjects were acceptable in private homes, relatively few were produced. Further, there was an artistic subject hierarchy based quite simply on what would sell. Paintings of this era, therefore, tend to have carefully orchestrated “scenes” in which ordinary life would appear better than it indeed was. In the case of Vermeer, ordinary life took on an empyrean glow, the subjects marinated in perfectly executed light and rich, extravagant pigments. Every detail was meticulously attended to.

Vermeer paintings are incredibly rare, with only 32 known works. They are also highly coveted. If you want to see “The Music Lesson” you will have to ask the Queen of England as she has it hanging in Buckingham Palace outside the view of the general public. Only one Vermeer has come to auction in a hundred years and it sold for 30 million dollars.

Painting, at this time was taught through formal apprenticeships that are well documented; yet there is no record where, to whom, or even if, Vermeer was apprenticed. There is also no record of any type of formal art education. When advanced technologies, such as x-ray, allowed historians to learn more about an artist’s methods it came as a surprise that none of Vermeer’s paintings contain any underlying sketches or grids, as did all of his contemporaries. Further, there are no known sketches or studies for his works.

Recent research has cast Vermeer in a different light. Not only was he nothing like the wildly fictionalized depiction in the book and movie “Girl With The Pearl Earring”, but he was very likely less a painter in the traditional sense, and more a combination of a technician and painter, utilizing completely different methods to achieve the astounding and unique beauty in his pieces. This might actually explain why he was omitted from art history for a long period of time. As this research unfolded, it became clear that at the very least Vermeer was less than conventional in his methods.

In 2001, British artist David Hockney published the book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, in which he argued that Vermeer used optics, specifically some combination of curved mirrors, camera obscura and camera lucida, to achieve precise positioning in his compositions.

Working independently, in 2001 British professor Philip Steadman published the book Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces, which specifically postulated that Vermeer had used a camera obscura to create his paintings. Most notably, Steadman found that six of his paintings, all painted in the same room, are precisely the right size and proportion if they had been painted from inside a camera obscura against the room’s back wall.

Someone with no art skill whatsoever, however, conducted perhaps the most impressive research into Vermeer. In 2008, American entrepreneur and inventor Tim Jenison developed the theory that Vermeer had used a camera obscura along with a “comparator mirror”, which is similar in concept to a camera lucida but much simpler, and allows for easily matching color values. He later modified the theory to simply involve a concave mirror and a comparator mirror.

He spent the next five years testing his theory by attempting to re-create The Music Lesson himself using these tools. He meticulously recreated the room at Oude Langendijk in a California warehouse. He created each element depicted in the painting in excruciating detail. He studied the pigments of the era, and like Vermeer, mixed his own paints from scratch. Along the way he discovered various things. In Vermeer’s paintings, there is an asynchronously colored, blurred edge around objects. This is an anomaly known to be created by using optics. Further, certain curvatures of objects that were expected to be straight within paintings suggested the use of curved mirrors. The mirrors exposed amazing details within every object being painted. Lastly, by using a “comparator mirror” the translation of color, size, position, and proportions, were no longer subjective but rather very objective translations.

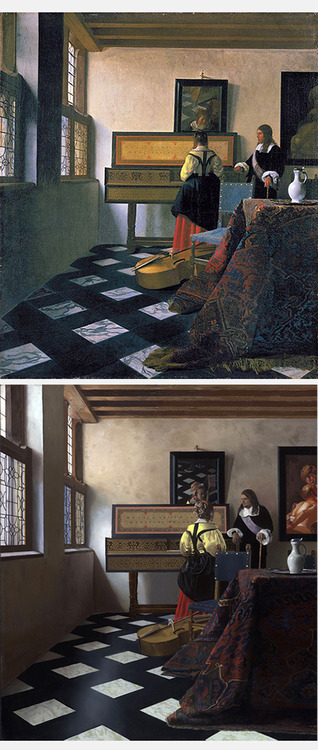

Jenison didn’t go after just any Vermeer, but rather what might be the most complex painting he ever did. Here’s the result:

Vermeer is at top, Jenison is at bottom:

Jenison, a man who had never painted a painting before spent the better part of everyday for a period of nine months working on his Vermeer. When he was finished and the painting was varnished in the same methods used in the Dutch Golden Age, he took his painting to a renowned art critic in England who declared it “better than a Vermeer” in almost every way. Jenison has almost definitively proven that Vermeer utilized optics to create his works and acted more as a technician than what was traditionally accepted as an artist.

So here’s the question: Should Vermeer be ejected from art history? Decried as a cheater? You can answer that yourself but do me this one favor; if you are fortunate enough to be one of the very few people to see a rare Vermeer in person, step back from it, forget everything you just read and behold what is one of the most beautiful, and beautifully rare works of art ever created. And believe that indeed, you can paint with light.